On Walls That Have Not Been Pulled Down: A Few Remarks Regarding the Ghetto Wall in Polish Cinema

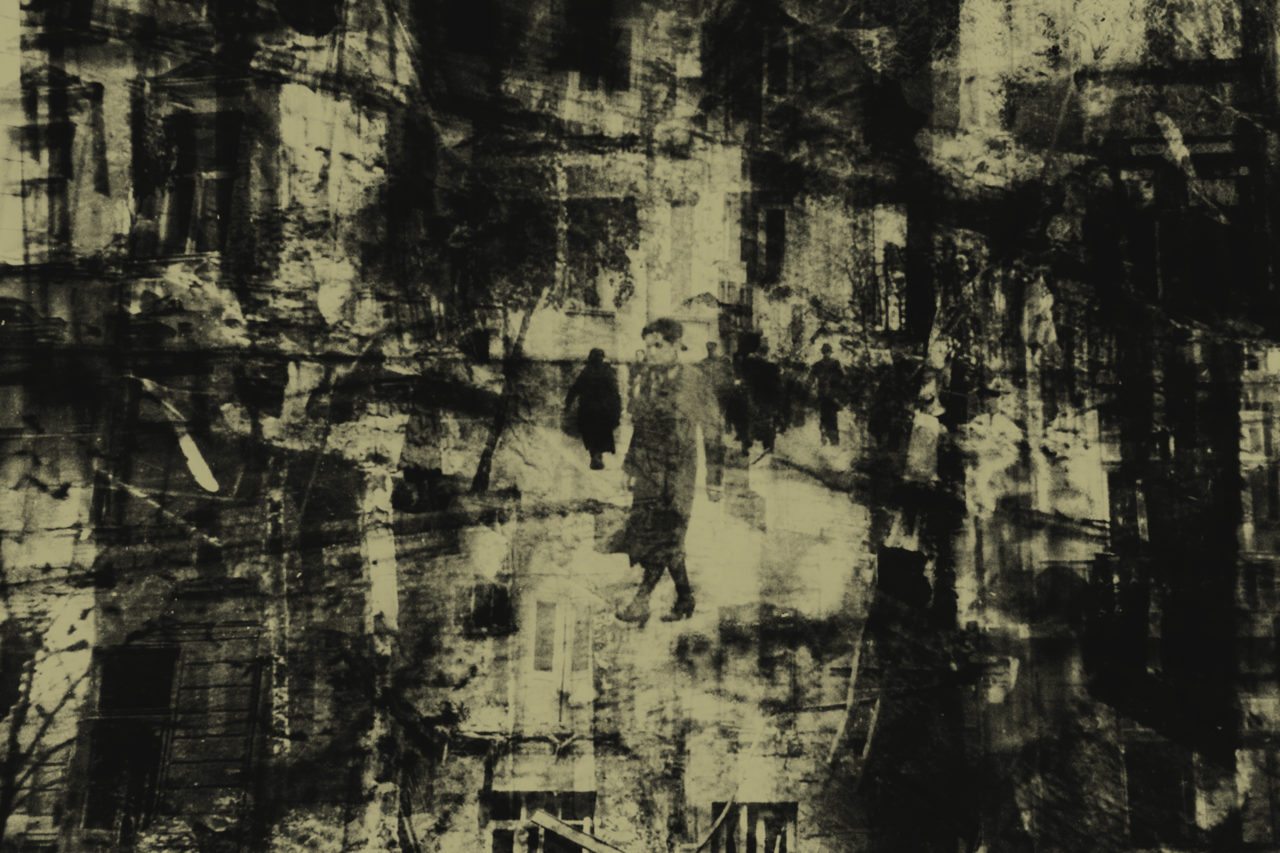

In his memoirs published right after the war, Władysław Szpilman wrote: “But the streets of the ghetto led nowhere. They always ended at the wall. I often happened to be walking forward to unexpectedly encounter it. It suddenly barred the way and even if I wanted to continue my journey, there was no logical explanation as to why it was not possible. The rest of the street, on the other side of the wall, became something in me that I could not give up, something dearest to me in the world and I would have given everything I had to experience the things that were happening there.” In Szpilman’s memoirs, the wall of the Warsaw ghetto is like a fresh wound, a bleeding scar of the city, which shuffled all known trails and broke the bonds of pre-war friendship. Szpilman’s diaries, published for the first time in 1946 edited and with an introduction by Jerzy Waldorff, were to be one of the first wartime memoirs to be filmed. The script was developed by Jerzy Andrzejewski and Czesław Miłosz, who gave their project a meaningful title: The Robinson of Warsaw. The lone composer hiding in the ruins of Warsaw was supposed to be the Robinson (the creators wanted to start making the film before the ruins were cleared up). Finally, in 1950, the unbearably ideological Miasto Nieujarzmione (Unvanquished City), directed by Jerzy Zarzycki, in which no traces of the original project remained, premiered in theatres. Miłosz and Andrzejewski had their names removed from the opening credits. The story of Władysław Szpilman had to wait 57 years to be told on the screen by Roman Polański. Polański achieved creative mastery: the set design, the costumes, the smallest details of the reality under German occupation created an extraordinarily coherent mise-en-scène. With his set design, emphasising the claustrophobic shrinkage of the ghetto world, Allan Starski created nearly palpable airlessness. The wall appears many times and is always an ominous sign. When Szpilman’s family moves into the apartment, they all watch the wall being erected, brick by brick. The noose tightens over time: “(…) the area was consistently reduced, similarly to the territorial changes occurring in Europe, where the German conquest moved the borders dividing the continent into two parts, the free and the occupied one”, he will write in his memoirs. Saved by a Jewish policeman, the protagonist walks through deserted streets as if he is on his deathbed – a half-alive, emaciated wreck of a man, passing by some tangled threads, utensils left after the Grossaktion. He tears down the wall – a symbol of oppression. But it is not a gesture of unifying the divided world, but of burying the unburied – the anamnesis of their existence.

The cinematic fate of Janusz Korczak’s diaries was similar to that of Szpilman’s story. The author of the first project was Ludwik Starski (Allan’s father). The diaries survived and Starski submitted a project to Film Polski studio; due to censorship, the film was never made in communist Poland. Aleksander Ford, who made an attempt to film the story of the Old Doctor in the unfortunate political situation of March ’68 was one of the first readers of Starski’s draft. Under the pretext of a delay, the production was brought to a halt. The set was basically already waiting in the studio on Chełmska Street. The wall was also there. Andrzej Wajda saw the moment of the hasty dismantling and disassembling of the already set up decor: “I have never seen anything like it and I hope I will never see it again in my life”, Wajda recalled. There may be no other scene as moving in the history of Polish cinematography. The year 1968 – the dry pogrom and the final exile of the survivors and their children. The wall, a scenographic simulacrum of the division, is dismantled. Paradoxically, the dismantling is a historical mystification. It is not a gesture of conciliation, but an annihilation of memory. One year later, Nazi images of the construction of the wall were used by Moczar’s propagandist, Janusz Kidawa, in Sprawiedliwi (The Righteous) (1969) – a post-March falsification in which the voice of the narrator informs the audience that Polish construction workers smuggled tons (literally!) of food to help their Jewish companions in misery. And Ford – difficult, autocratic but unjustly hurt – leaves to make the film about Korczak abroad, Sie sind frei, Doktor Korczak (You are free, Doctor Korczak), a failed and forgotten work. In 1980, after a series of personal and professional failures, he commits suicide. Before that, however, he manages to create a kind of epicedion for Polish Jews (he lived through the war in Soviet Russia) in Ulica Graniczna (Graniczna Street), which premiered in June 1949. The set was made in Barrandov in Prague, and partly in the streets of Łódź. The wall was built in the Prague studio. The film received mixed reviews. There were critical voices, accusations of defeatism (why is the Holocaust so pessimistic?). Maria Dąbrowska, who attended a pre-premiere screening will write in her Dzienniki (Journals) that it is anti-Polish. It has difficulty breaking through to the public, and the Jewish identity of the protagonists is watered down by waves of leftist universalism. In Ford’s film, the wall is not a border that predestines one to life or death. It is merely a physical barrier – when we overcome it, we partake of a certain ethical fulfilment to which, in the communist imaginary, we are predisposed.

Paying no heed to communist censorship, Andrzej Wajda created one of the most important films about the ghetto, Samson (1961), based on the novel by Kazimierz Brandys. We see the wall in long shots which clearly separate Jewish and Aryan Warsaw. The winter aura underlines the lifelessness of the world. In the almost fairytale-like camerawork of Jerzy Wójcik, Jakub Gold, played by Serge Merlin, pushes a flatcar as fake snowflakes fall on the bodies emaciated with cachexia. In the shot, Wajda uses unique linear narration – much like in the entire diegesis, which follows a strict plot.

What is on the other side of the frame divided by the wall? In Samson it is emptiness. Not the phantasm of a happy, Aryan Warsaw – only a similar dark abyss and uncertainty.

The wall appears many times in Korczak, filmed over 30 years later. Korczak (played by Wojciech Pszoniak) looks at the Aryan side and sees a guard. Who is he? What is he guarding? – he asks himself. The doctor looks at the lazy guarding routine with an empathetic naivety, trying to see the good in the watchman. This is the price we pay for the illusions we succumb to when reality is brutally different from our Weltanschauung.

The wall obliterates individuality, uniqueness, and social status. It kills dignity. Like a roller, it levels all phantasms of assimilation and fits people into racial compartments. The wall feeds on fear and states that human beings are as humane as we allow them to be. Nevertheless, there were exceptions: it was possible to be someone like Korczak, before whom – as Hannah Ardent put it – “the possibility opened of becoming something highly unnatural, namely a man”. Those who wanted life were the ones who left the wall. The wall was also crossed by those running from death on the Aryan side, yearning for a “Jewish death”. Irena Lilien from the short story by Andrzejewski, adapted by Wajda in his film Holy Week, returns to the ghetto. She walks past laughing German soldiers and returns to the ashes. Returns to the ghetto were not unheard of. They represented the choice of a dignified death, without the burden of being blackmailed by shmaltsovniks, a death characterized by human and ancient dignity – ars moriendi.

Ghetto crowds, hemmed in by the wall, can be seen in Wniebowstąpienie (Ascension) (directed by Jan Rybkowski, 1969), in Kartka z podróży (Postcard from a Journey) (directed by Waldemar Dziki, 1983), Tragarz puchu (Warszawa. Année 5703) (directed by Jan Kijowski, 1992) and in Jeszcze tylko ten las (Just Beyond This Forest) (directed by Jan Łomnicki, 2005) in which the wall is crossed by a child protagonist and her Polish chaperone. The journey sets in motion their odyssey towards death. Getting across the wall does not mean salvation. It is merely the beginning of a journey through the Hades of the “Bloodlands” of the Generalgouvernement, during which the protagonists abandon their Jewish identity. They must draw oblivion from Lethe to resist the rushing waters of the Styx.

In Polish cinematography, the ghetto wall constitutes a physical barrier, a separating border defining the phenomenology of Jewish death. It is also a piece of decor, set up with the gestural automatism of accepted Holocaust topoi which determine the topographic division into the Jewish and Aryan side. But the thing beyond the decor itself is the story of the creation of these sets. Their existence and demolition. In the hallucinatory imaginary, this is what shapes Polish dreams about the wall. The eleven original fragments of the wall in Warsaw which have survived until the present day have never been used in a film. The only wall featured was part of a set, a false reality created to serve as a background for a fictional story. Here, we could go off on a tangent about how film, due to the nature of its genre, is only a dream about reality, giving audiences the illusion of participating in the latter. But we can also look at the history that manifests itself in these cinematic texts as a dream dreamt by a certain community, a kind of paradox at variance with the historical record. In the television series Śmieciarz (Rubbish Collector), Kolumbowie (The Columbuses), Sprawiedliwi (The Righteous), Czas Honoru (Days of Honour) the wall is not an insurmountable barrier. It is an obstacle but also a challenge for the heroic Polish narratives.

If Polish cinematography is an art from which any consideration of the seclusion created by the wall is absent, if these discourses posit “Aryan” and “Jewish” Warsaw as communities clasped in a conciliatory embrace, where the loneliness of those who are dying always finds a supportive Polish shoulder – that perspective is false. But memory relies not only on what is, but also on what never was and never manifested itself to the world. And the rasp of saws dismantling the Styrofoam wall from the set of Ford’s failed film about Korczak, heard by Wajda in the gloomy spring of 1968, is a tale of walls that are still being erected – walls that do not want to be pulled down.

Bartosz Kwieciński – assistant professor at the Department of Political Journalism, Institute of Political Sciences and International Relations of the Jagiellonian University. Film historian, media expert and author of the monograph Obrazy i klisze. Między biegunami wizualnej pamięci Zagłady (Images and Clichés: Between Opposite Extremes of the Visual Memory of the Shoah) and articles about the formation of memory about the Holocaust. Holder of national and international grants. He is currently working on a monograph on the attitudes of the Polish intelligentsia in a liminal situation (1981-1990).