The Warsaw Ghetto Wall as the Axis of the Space of Life and Death

“Could you see anything on the Aryan side over the wall?”

“Yes. The wall reached only to the first floor. From the second floor, you could see THAT street.”1

Before World War II, Warsaw was a city with the largest Jewish community in Europe and the most important centre of Jewish culture. During the war years, the Germans established the largest ghetto in what was known as the Northern District. Some 400,000 Jews found themselves inside its walls. In April 1941, when deportees from nearby towns and a group of Jews from Germany arrived in the ghetto, the number of inhabitants increased to about 450,000. Since the creation of the Warsaw ghetto, people’s lives were threatened by hunger, diseases, poor housing conditions, slave labour, and being despoiled by the German authorities. Terrible conditions inside the walls led to the death of about 92,000 people by July 1942. As a result of the Grossaktion, between 22 July and 21 September 1942 about 75% of the ghetto’s inhabitants were deported to the Treblinka extermination camp and murdered there. The total number of victims of the Warsaw ghetto is estimated at 400,000 people (about 300,000 were killed in Treblinka and during two deportation operations).2.

*

The memory of this place and of the tragedy it witnessed was recorded in the accounts of survivors, memoirs, private diaries and journals, documents, and correspondence. Extensive historiography on the Holocaust, detailed historical and sociological writings, as well as publications dealing with contemporary attitudes to the Shoah in theology, memoir literature, music, and the visual arts show how necessary research into memory and its representations is.3, show how necessary the research into memory and its representations is.

Reading memoirs, notes, oral and written reports stored in the archives of the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw and, for example, at the State Archives in Łódź, some of them very personal, relating individual experiences and particular cases, repeatedly confronts us with the image of two “sides” often presented in survivor accounts. The ghetto is one side, and the so-called Aryan side is the other. They are separated by a WALL. The image of the wall is a recurring theme in the memoirs of Holocaust survivors, but it is also present in historical studies, literature, and the visual arts. A fence, barbed-wire entanglements, a brick wall; the wall that separates, isolates, closes, spiked with broken glass, interrupted only by gates with armed guards, became the Leitmotif of the stories told by those who survived and, at the same time, the image and idiom of the Holocaust.

In 1940, the Germans drew up a detailed plan to divide Warsaw into three districts: Jewish, Polish, and German. The decision concerning the Jewish district came into force on 15 November 1940. On 16 November 1940, the Jews of Warsaw were locked in the ghetto surrounded by a high (reaching the first floor) wall with barbed wire entanglements. Describing the topography and communications of the Warsaw Ghetto, the position and changes to its borders from September-November 1939 to April-May 1943, Barbara Engelking and Jacek Leociak write:

“The culmination of the division of Warsaw is undoubtedly the emergence of a dichotomy: ghetto side – Aryan side. It is not only the most characteristic feature of the urban space at the time but also a specific existential space, founded on the distinction between “this” and “that” side. The axis of this space is the wall.”4

*

I would like the main motif of this text to be a scene from Roman Polanski’s film The Pianist, faithfully based on Władysław Szpilman’s memoirs written after the war and published as Pianista. Warszawskie wspomnienia 1939-1945 (the first edition, entitled Śmierć miasta, was prepared by Jerzy Waldorff and published in Warsaw in 1946; the second edition came out in Warsaw in 2000 and differed significantly from the first one; an edition prepared and with an introduction by Andrzej Szpilman and an afterword by Wolf Biermann was published in Cracow in 2002). Both Szpilman’s post-war memoirs and Polanski’s film adaptation present the events in the Warsaw ghetto from the perspective of a single person – a direct witness and participant of the events. The personal message delivered by Szpilman, the “war pianist” (as he called himself) does not reflect the complicated reality of wartime, but movingly illustrates the extreme experience of an individual faced with a tragedy that leaves him powerless and helpless. Historians try to reconstruct the real picture of life in the ghetto, taking into account all the testimonies to which they have access, which they have gathered and analysed, from which they try to reconstruct the facts. Szpilman’s memoirs consisting of chronologically arranged sequences, were turned into a vivid and suggestive narrative in Polanski’s film.

Szpilman’s account includes a scene that he remembered and recorded in detail in chapter six, The Hour of the Children and the Mad (pp. 60–69). At the time, the artist was working as a pianist at Nowoczesna café on Nowolipki Street:

“To get to the café I had to make my way through a labyrinth of narrow alleys leading far into the ghetto, or for a change, if I felt like watching the exciting activities of the smugglers, I could skirt the wall instead. […] Restless figures appeared in the windows and doorways of the blocks of flats along the wall and then ducked into hiding again […] and as a horse-drawn cart trotted past the agreed signal, a whistle, would be heard, and bags and packets flew over the wall. […] The ghetto walls did not come right down to the road all along its length. Certain intervals there were long openings at ground level through which water flowed from the Aryan parts of the road into gutters beside the Jewish pavements. Children used these openings for smuggling.

[…]

One day when I was walking along beside the wall I saw a childish smuggling operation that seemed to have reached a successful conclusion. The Jewish child still on the far side of the wall only needed to follow his goods back through the opening. His skinny little figure was already partly in view when he suddenly began screaming, and at the same time, I heard the hoarse bellowing of a German on the other side of the wall. I ran to the child to help him squeeze through as quickly as possible, but in defiance of our efforts, his hips stuck in the drain. I pulled at his little arms with all my might, while his screams became increasingly desperate, and I could hear the heavy blows struck by the policeman on the other side of the wall. When I finally managed to pull the child through, he died.”5

This suggestive record of personal experience, a shocking episode from the Warsaw ghetto, in which Szpilman paints a picture of the fate suffered by Jewish children and describes in detail the death of a little smuggler, becomes a metaphor in Polanski’s work. At the same time from the perspective of the contemporary viewer it seems to lose the “fictionality” of a film representation, gaining the status of a historical subject. Analysing the issue of how evil is presented in terms of ethical content and artistic form, Berel Lang puts forward the claim that when the moral consequences of a subject (a scene from the film in this case) “are extreme, it should not come as a surprise that the representation must include an element of ethical judgment”.6. The very fact of taking up the subject of extermination in the visual arts involves moral judgment, since it suggests that the creative act as such (whether in literature, music, film, painting or sculpture) can frame something that would otherwise (i.e., if it had not been recorded, reproduced, or painted) remained undisclosed. It therefore reveals facts hidden by the perpetrators of the Holocaust. The Holocaust as a subject refers to an extreme situation. “[E]very element of representation, including the act of representing itself, becomes morally significant”7, writes Lang.

The “truth” of the brick wall, along which Władysław Szpilman (Adrien Brody) walks in The Pianist, which in this case represents the Warsaw ghetto wall, is defined by its infinity (it stretches as far as the distant horizon). The blue and grey darkness is “rarefied” by the rhythm of burning lanterns, the narrow pilasters reinforcing the walls suggest claustrophobic enclosure. The height of the wall, contrary to the account of Marek Edelman who mentions that it reached the first floor, seems to have no end, completely obliterating the sky. The closure of the ghetto is absolute, the people living on the other side are invisible, and those living within are completely alone in their will to survive. The reader of Szpilman’s memoirs knows what is happening on the “Aryan” side – the child whom the pianist wants to help get back to the ghetto is battered by a Nazi, we hear curses in German and the sounds of beating. In Polanski’s film, the wall separates us from the world beyond, we don’t see the child’s murderer (although we know who he is) – we see a boy trying desperately to slip through a tunnel dug under the brick wall, we hear the blows, the cries of the little smuggler, the futility of the effort to save him. The child dies in the man’s arms, the road along the wall he was walking seems to have no end.

The Nazi genocide was depicted in one sequence, where the wall was presented as a monolith, and at the same time, it represented the personification and the truth of closure, isolation, loneliness, the impossibility of crossing or recognising the world behind it. The reality of the Warsaw Ghetto during World War II, surrounded by barbed-wire entanglements, boards with German warnings about typhus written on them, is isolated from the “Aryan” side. The longitudinal holes under the walls, serving as gutters for the sewage flowing from the “Aryan” side, through which children were smuggling food into the ghetto, make us aware of the immeasurable contempt of the Germans, who treated the ghetto area as a garbage dump.

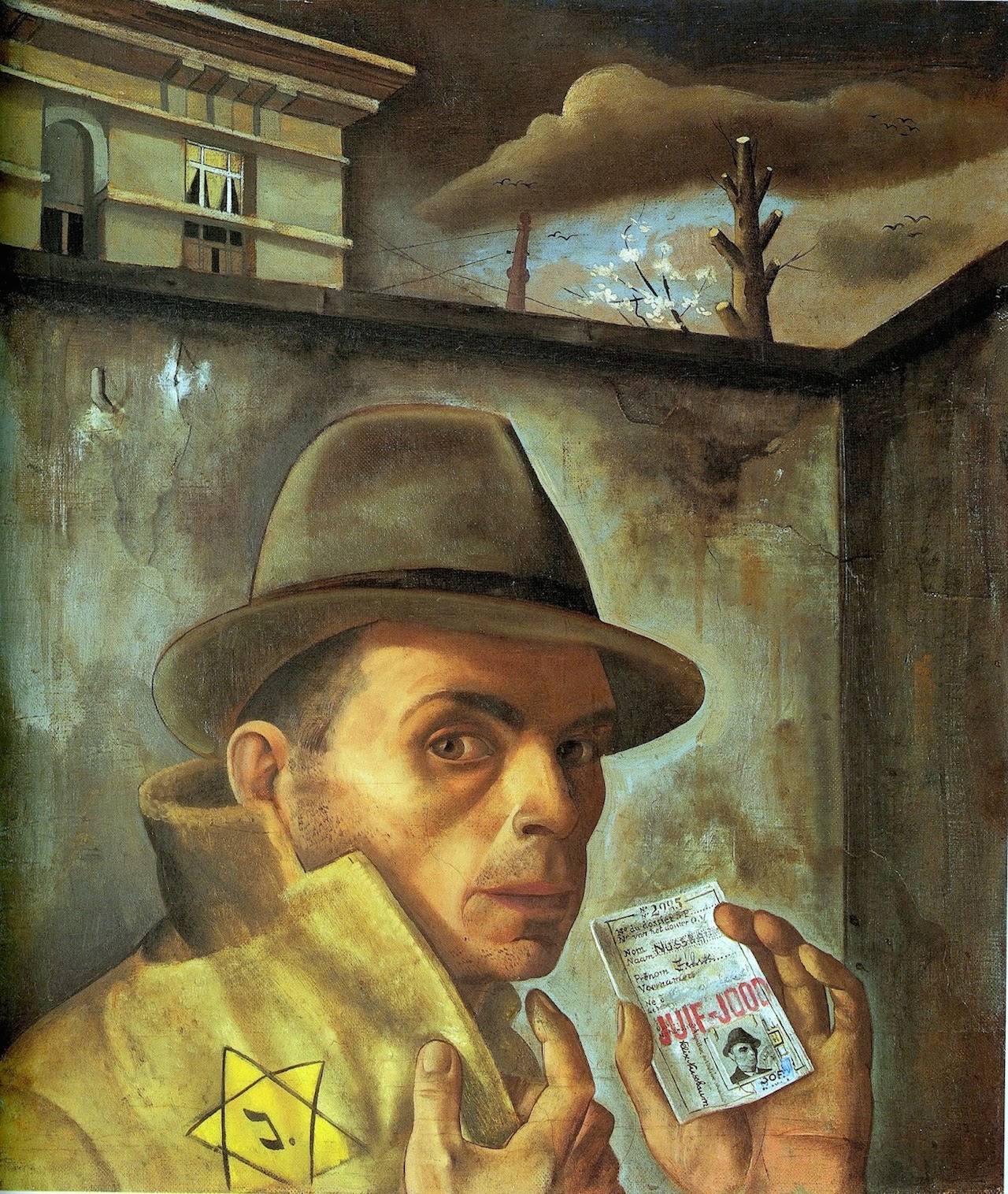

In the memoirs of Holocaust survivors, life outside the ghetto is often portrayed as radiant, carefree, with girls in bright dresses walking the streets of Warsaw and stalls full of fruits and flowers. The separation of those inside the Warsaw ghetto from those on the “Aryan” side seems complete. The metaphorical message of the image engraved in the memory of the Holocaust survivor and replicated in Polanski’s (also a Holocaust survivor) film image gives it the quality of a universal drama of isolation and exclusion. The rupture of reality, the void between “behind” and “in front of” is filled with the impossibility of bearing witness to the truth, the “inability to testify”8, as Giorgio Agamben put it. The wall separating the two worlds in film or painting (e.g., Felix Nussbaum’s Self Portrait with Jewish Identity Card, ca 1943)9 is a symbolic indication of the inability to testify – “neither from within, it is impossible to testify from inside of death, there is no voice that can express the silence, nor from outside, because an outsider is by definition not involved in the event”,10 Agamben writes.

Image source: https://artpil.com/felix-nussbaum/ [accessed: 25.09.2020].

A special example of the metaphor of the wall in painting is the above-mentioned self-portrait by Felix Nussbaum (b. 1904 in Osnabrück, d. 1944 at Auschwitz) painted in 1943, a year before Nussbaum’s death. The painting shows a realistically depicted young man in a hat, with a clearly visible yellow Star of David with the letter “J” sewn onto his coat. While the painter reveals the stigmatizing emblem with one hand, with the other he demonstrates his identity card, certifying his belonging to the Jewish people: “JUIF-JOOD”, photograph, signature, short description, and identification number. The lone man, carefully staring into the eyes of the viewer, is surrounded by a high wall, above which only the top floor of a tenement house is visible, a tree trunk with the branches sawn off, a telegraph pole, blackbirds against the background of a cloudy sky. Nussbaum was killed on 2 August 1944 at Auschwitz. In 1943 he was still hoping to survive in hiding. This hope is symbolized by a fragment of the tree crown blooming with white flowers on the other side of the wall. The wall in Szpilman’s picture-memory and in Polanski’s film is a special reference to historical truth (fragments of the wall have survived in the topography of contemporary Warsaw and testify to the past). In Nussbaum’s painting, the wall has a metaphorical meaning – the artist used it to express his own isolation, loneliness, and sense of threat and resignation.11.

*

Szpilman’s record is a memory, something available to memory, so when relating events from the ghetto, the author knows (just like the contemporary reader) what consequences these events had. The fate of the author himself is also known. As testimony, the events taking place “behind” and “in front of” have been confrimed by historical research. Nussbaum’s painting is a testimony “impossible to correct” – it represents the emotional experience of the artist, it is unconditionally authentic, although it does not indicate historical truth – no walls or fences were erected in Brussels to separate Jews from non-Jews. The wall of loneliness and exclusion was created by abandonment, hostility, and the sense of danger. The empty and silent windows of the building visible in the background symbolize indifference and abandonment.

When addressing the subject of the wall (here the wall of the Warsaw ghetto) as a synonym of exclusion and isolation, one should bear in mind the importance of the past, which is closely related to the present. The past has conditioned our modernity; the wire entanglements will continue to be built, they will separate one kind of people from another, they will symbolize isolation and segregation. However, having this one wall in mind – the wall that tore the city apart for five years and has left traces of an invisible border to this day, maybe we will try to limit our phobias and fears in favour of conversation, opening, and communication.

Hanna Krall, Zdążyć przed Panem Bogiem [To Outwit God], Kraków 1977, p. 12 ↩

https://1943.pl/historiagw/ [accessed on: 8.10.2020]. ↩

Cf. Tomasz Majewski, Anna Zeidler-Janiszewska, Maja Wójcik (eds), Pamięć Shoah. Kulturowe reprezentacje i praktyki upamiętniania, Łódź 2009. ↩

Barbara Engelking, Jacek Leociak, Getto warszawskie. Przewodnik po nieistniejącym mieście, Warszawa 2001, p. 69 (69–113). ↩

Władysław Szpilman, The Pianist: The Extraordinary True Story of One Man’s Survival in Warsaw 1939-1945, transl. Anthea Bell, London 1999. ↩

Berel Lang, “Przedstawianie zła: etyczna treść a literacka forma”, transl. Anna Ziębińska-Witek, Literatura na Świecie 2004, nr 1–2, p. 22. ↩

Ibid. ↩

Giorgio Agamben, “Co zostanie z Auschwitz. Archiwum i świadek”, in: Homo sacer III, transl. Sławomir Królak, Warszawa 2008, p. 35. ↩

The painting is in the collection of the Osnabrück Kulturgeschichitliches Museum. ↩

Giorgio Agamben, op. cit., p. 35. ↩

After Hitler came to power in 1933, Nussbaum and his wife, painter Felka Płatek, were granted asylum in Italy, then in France, and from 1937 they lived in Brussels. Two days after the German army entered Belgium, the local authorities issued a warrant for his arrest and transfer to the internment camp in Saint-Cyprien in the south of France. After a successful escape, he returned to Brussels, where he met with his wife. Both of them hid at a friend’s, who was an art dealer. Following a denouncement, they were arrested and imprisoned in Mechelen. They both probably perished on the same day (2 August 1944) at Auschwitz-Birkenau. ↩

Eleonora Jedlińska – Dr habil., professor at the University of Łódz, lecturer in art theory, art criticism and the history of modern and contemporary art, member of the AICA since 1996, president of the Łódz Branch of the Polish Institute of World Art Studies, member of the European Association of Jewish Studies and the World Union Jewish Studies in Jerusalem. Author of numerous publications, including: Sztuka po Holocauście (Art after the Holocaust), Polska sztuka współczesna w amerykańskiej krytyce artystycznej w latach 1984-2002, (Polish Contemporary Art in American Art Criticism 1984-2002), Powszechna Wystawa Światowa w Paryżu w 1900 roku. Splendory Trzeciej Republiki, (The 1900 Universal World Exhibition in Paris: The Splendours of The Third Republic) and Kształty pamięci. Wybrane zagadnienia sztuki współczesnej (Shapes of Memory: Selected Aspects of Contemporary Art).